GreehouseTruth Blog :: Hurricane 2006, Fade to Black

|

|

|

|

|

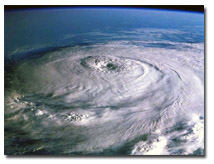

Hurricane 2006, Fade to Black

Pondering this year's quiet tropical storm season

Posted October 22, 2006 by Nathan Cool

With understandable anxiety left over from 2005 while eyeing signs of another potentially strong hurricane season, forecasters compiled reports in the spring of 2006 warning residents along the fringes of hurricane alley to hunker down for another doosey of a year. Having expectations of Katrina-like storms, households stockpiled ready-to-eat meals, canned goods, bottled water and gas-powered generators. Fear ran rampant through the stock market sparking an unease that drove oil prices to all-time highs. While NOAA advocated the presence of a naturally occurring decadal oscillation conducive for powerful storms, alarmists were quick to link global warming to hurricane ferocity--a feeling shared by many after enduring the devastating seasons of 2004 and 2005. But then something unexpected happened: nothing--all went quiet as though someone flicked a switch and the room went quietly dim. Philip Klotzbach, author of well-known hurricane season predictions from Colorado State University, provided an apologetic avowal by quoting the 19th-century mathematician Francois Arago: "Never, no matter what may be the progress of science, will honest scientific men who have regard for their reputations venture to predict the weather." But the ho-hum hurricane season of 2006 wasn't isolated to a single storm or weather event--we're talking about a year's worth of storms. We're talking about climate. And in a world that is warming, many are now left wondering just what in the heck happened.

With understandable anxiety left over from 2005 while eyeing signs of another potentially strong hurricane season, forecasters compiled reports in the spring of 2006 warning residents along the fringes of hurricane alley to hunker down for another doosey of a year. Having expectations of Katrina-like storms, households stockpiled ready-to-eat meals, canned goods, bottled water and gas-powered generators. Fear ran rampant through the stock market sparking an unease that drove oil prices to all-time highs. While NOAA advocated the presence of a naturally occurring decadal oscillation conducive for powerful storms, alarmists were quick to link global warming to hurricane ferocity--a feeling shared by many after enduring the devastating seasons of 2004 and 2005. But then something unexpected happened: nothing--all went quiet as though someone flicked a switch and the room went quietly dim. Philip Klotzbach, author of well-known hurricane season predictions from Colorado State University, provided an apologetic avowal by quoting the 19th-century mathematician Francois Arago: "Never, no matter what may be the progress of science, will honest scientific men who have regard for their reputations venture to predict the weather." But the ho-hum hurricane season of 2006 wasn't isolated to a single storm or weather event--we're talking about a year's worth of storms. We're talking about climate. And in a world that is warming, many are now left wondering just what in the heck happened.

One of the most contentious topics of climate change is hurricanes. While there has been extensive research in recent years to find connections between storm intensity and a warming world, the results are still very much inconclusive--something I discuss at great length in chapter 5 of Is it Hot in Here?--The simple truth about global warming. The primary reason that hurricanes continue to lack well-founded ties to climate change, is that hurricanes are products of weather, not climate. Although climate and weather are inextricably linked, climate is a product of time spans whereas hurricanes are unique, singular events. When looking back over an entire season though, climatology does come into play. A better view is revealed over even longer spans of time. This gives climatology better hindsight than foresight, making weather-event forecasts extremely difficult to formulate. Yet there are other flies swimming around in the proverbial ointment as well.

One of the most overlooked snags in tying hurricanes to global warming is the temperature difference issue: hurricanes need not only warm water, but also a great difference in temperature between water and the air above it. Without a relatively cooler atmosphere, rising hurricane columns won't accelerate quickly and usually just peter-out. In a world that is warming, both air and sea temperatures rise. Although water temperatures become warmer than normal, the air too becomes quite warm; hence, the difference between the two remains the same. When the water becomes warmer than the air, then trouble looms on the horizon. But this would not necessarily mean global warming per se; instead, such an event could be considered ocean warming. When land, sea, and air temperatures increase, then we're looking at a global warming. But, when that happens, the differences between seawater and atmosphere remain relatively small. This was one of many factors that played a role in recent hurricane seasons, and was one element involved in the subdued hurricane season of 2006.

In May 2006, NOAA's Climate Prediction Center issued an Atlantic Hurricane Outlook Report calling for "a very active" 2006 season with 13-16 named storms, 8-10 hurricanes, and 4-6 major hurricanes. Forecasters from the Department of Atmospheric Sciences at Colorado State University issued a similar report. The ominous predictions contained in these forecasts were primarily predicated on an active, naturally occurring multi-decadal oscillation that started around 1995, above average Atlantic Ocean temperatures, and a neutral ENSO (neither an El Niño nor a La Niña were developing at the time). But as the summer season got underway, Mother Nature threw a few curveballs, which affected these forecasts.

Although we are indeed in a naturally occurring decadal cycle conducive for hurricane formation, ocean temperatures dropped this past summer. One reason, ironically also related to climate change, was an excessive amount of Saharan dust that blanketed the skies over the eastern Atlantic off the coast of Africa where many hurricanes originate. As severe drought continued in Saharan Africa, windstorms swept massive amounts of sand and fine-grained grit skyward, where it sat and swirled about for weeks. This caused a global dimming effect that cooled the eastern Atlantic waters, thus reducing the warm-water fuel needed for hurricane formation. On top of that, Atlantic ocean temperatures decreased overall, and for some reason or another, ocean temperatures were found to be on the decline worldwide in the past couple years--something that goes against the alarmist grain, which I elaborated more on in another blog article that you can read here.

As ocean waters cooled this summer, the ENSO cycle took an unexpected turn towards El Niño. Such an event, which I discuss in greater detail in chapter 3 of Is it Hot in Here?, can lower the jetstream enough that vertical wind shear increases--something that is bad news for hurricanes trying to form. But the cooling of the waters and the cycle towards El Niño is not necessarily optimistic news for the climate.

In both cases, global warming may have played a role. In the case of the cooler than average waters, dust that was likely brought on by climate change negated hurricane formation. And the second factor (ENSO swing) is a little disquieting, since we were in an El Niño in 2004, a La Niña in 2005, and now an El Niño again in 2006. El Niño cycles typically last 2-7 years. In a warming world though, it's thought that these types of events could occur with greater frequency.

Elsewhere around the globe, tropical cyclones did cause problems. The Western Pacific has been rather busy, and some storms have wreaked havoc on Asian countries. The Eastern Pacific has had its share of storms as well, although most have remained rather benign. Hurricane season is still not over yet, and the proverbial fat lady doesn't sing until November 30. Still, NOAA and other forecast offices have downgraded their reports, and it looks like the worst may be over for this year.

Will future years see a return of 2005? Will we see stronger, Katrina-like hurricanes in the future? While some scientists say yes, others adamantly disagree, pointing to this year's punchless hurricane season as proof that as the world warms, hurricanes may not necessarily become more frequent or intense. Both views hold merit, especially the latter since the strongest recorded hurricane to make landfall in the U.S. happened way back in 1935--not 2004 or 2005. While Wilma last year broke an all-time record for Atlantic strength, it was only category 4 when it made landfall on the Yucatan Peninsula--the 1935 storm remained a category 5 when it slammed into the Florida Keys. Other strong, category 4 storms hit Texas in 1886 and Florida in 1919--long before the onset of the gas-guzzling SUV. In fact the three strongest landfalling hurricanes (category 5s) in the U.S. hit in 1935 (unnamed), 1969 (Camille), and 1992 (Andrew). The majority of category 4 storms hit between 1900 and 1961, bearing in mind that hurricanes have only been recorded since 1851 and that stronger hurricanes may have occurred before this time.

But both views on whether hurricanes will become more intense over time are based on theory and climate models that are continually tweaked as scientists receive surprises from Mother Nature each and every year. It may feel good to breathe a sigh of relief now, as we seem to be ending this year's hurricane season on a sweeter note than last year. Yet the link between hurricane ferocity and global warming remains in question--one of many such difficulties in predicting the future of a warming world. Nevertheless, it's no time to let our guard down on hurricanes, and only time will truly tell if a cousin of Katrina lie in wait in the upcoming years.

|

To stay abreast on other articles like this one, you can signup for the free GreenhouseTruth newsletter. Additional information on hurricanes and climate change, global temperatures, and other topics discussed in this blog can be found in Nathan Cool's new book, Is it Hot in Here?--The simple truth about global warming. Click here to get your copy. |

|